Joan Eardley lived for her art. And for friendship. She wrote letters every day to her mother and to close friends. She loved music; Bach, Bartok, Beethoven, Mahler…

As her first biographer, art critic – and art school friend – Cordelia Oliver observed, Mahler’s “most anguished compositions must have echoed Joan’s own struggle to express the inexpressible in paint”.

We also know from Oliver’s book, published 25 years after Joan’s death in 1988, that she had a strong magnetic personality and her loyal friends stuck to her through thick and thin.

As Oliver records, being the object of veneration in a glittering urban art salon or exhibition opening was painfully uncomfortable for her old art school pal.

To prove this point, Eardley wrote a letter to her friend Audrey Walker from London in May 1963 – three months before her death – following the private view of her one-woman show at Roland, Browse, Delbanco in Cork Street.

She described it like this: “Drinks flowing … oceans of champagne … the usual crowds – few of them ‘real people’ – as all true painters are, I think. It’s only the phoney ones who aren’t and that is interesting.”

Photos: Anthony Baxter

Fittingly, as Joan Eardley’s centenary year celebrations drew to a close last weekend, the life and legacy of this great Anglo-Scottish artist was celebrated in Arbuthnott village hall, just eight miles away from the clifftop village of Catterline in rural Aberdeenshire.

Around 100 people from all walks of life; from farmers to artists to teachers and more, gathered in this village hall beside the Grassic Gibbon Centre, to celebrate and commemorate the work of an artist who lived quietly among the folk of The Mearns.

At one point during the dinner, the grandson of Eardley’s closest Catterline friend, Mrs Taylor, who lived at No. 7 South Row, came up to say hello to Patrick Elliot, Chief Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the National Galleries of Scotland, and her niece, Anne Morrison-Hudson, who oversees the Eardley Estate.

It was that kind of night.

Both Patrick and Anne were guest speakers at this special night, which began with golden sunlight flooding in through the windows and ended with guests filing out into the darkness of the Mearns. In a most Eardley-esque turn of events, the nearby fields were flooded with light from a gibbous moon.

The Grassic Gibbon Centre celebrates the life, work and times of author James Leslie Mitchell. Under the pen name of Lewis Grassic Gibbon, Mitchell wrote 16 books, including his much-loved novel Sunset Song. He grew up in Arbuthnott and the centre is a place where his life and legacy are celebrated.

In Sunset Song, Gibbon’s young female protagonist, Chris Guthrie, felt most free among the land and big skies of The Mearns, as this historic patch of land along the North Sea coast south of Aberdeen is known.

As I pointed out in a short speech I made towards the end of the evening, both Eardley and Grassic Gibbon loved this land. Grassic Gibbon’s ashes were interred in the nearby Arbuthnott kirkyard, while Eardley’s ashes were scattered on the foreshore at Catterline.

Both died young. Grassic Gibbon aged 34 and Eardley at 42. Both were born on farms. Both had “the speak” of the land running through their veins. They loved the wildness of the land and sea in winter. Its beauty in summer. And they wanted to capture it for posterity. And at speed. Grassic Gibbon in words. Eardley in paint.

As Joan Eardley’s centenary year inches to a close on this day, Wednesday 18 May 2022, it’s time to mark 101 years since her birth in rural Sussex.

Plans to celebrate the centenary of this most singular artist were hatched in depths of lockdown in spring 2020 by a small group including Anne Morrison-Hudson, myself and Lynne Mackenzie, creator of this website. Anne offered to fund the creation of the website and social media dedicated to Eardley. This was our starting point.

In the lead-up to the centenary of such a popular and influential artist as Eardley, a retrospective might have been planned. Timing is everything in the art world, however, and in Eardley’s case, the National Galleries of Scotland had already held two major exhibitions of her work in Edinburgh; a retrospective in 2007 and A Sense of Place in 2016-17, which focused on drawings and paintings made in Townhead, Glasgow, and at Catterline on Scotland’s northeast coast.

The centenary might also have offered the opportunity for a major exhibition in Eardley’s adopted home city of Glasgow or even in London, where she lived from the age of five to 18. For various reasons, including the pandemic and the reopening of the Burrell Collection, this did not happen.

The game-changer for Eardley 100 came as communications started to whirr in the ether between a newly formed group called the Scottish Women in the Arts Research Network (SWARN) and the Eardley Estate.

Over the course of several months, as our lockdown locks grew longer, the number of arts professionals in SWARN grew in line and online alongside various plans from a growing roster of members looking to celebrate Eardley in her centenary year.

The celebrations kicked off on 29 April 2021 with an online symposium hosted by The Arran Arts Heritage Trail. The day commenced with an examination of Joan Eardley’s work and legacy on Arran hosted by broadcaster Kirsty Wark.

On the centenary of Joan’s birth, 18 May, a sparkling online birthday bash was organised by The Hunterian. Over 500 people joined the webinar from across the world for the event chaired with elan by BBC Scotland’s arts correspondent, Pauline McLean.

In the months which followed, a hive of small Eardley exhibitions opened at various venues, including:

- Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh (ends August 2022)

- Aberdeen Art Gallery, Aberdeen

- Rozelle House, Ayr

- Perth Museum, Perth

- Gracefield Arts Centre, Dumfries

- The Hunterian, Glasgow

- The Lillie, Milngavie

- Glasgow Women’s Library, Glasgow

- The City Art Centre, Edinburgh

- Lyon & Turnbull, Edinburgh

- The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh

- Mottisfont, Hampshire

- Dunoon Burgh Hall (until 12 June 2022)

The Tate’s one and only Eardley, Salmon Net Posts c.1961–62, is currently on display at Tate St Ives, Cornwall. Online exhibitions from Aberdeen Art Gallery and Glasgow Museums provided endless stay-at-home Eardley excitement.

Writing in the London Review of Books about Eardley’s work he saw in a handful of these exhibitions, eminent Scottish writer, Andrew O’Hagan, described Eardley as a “feverish, romantic successor to Goya and Soutine.”

Artist Kate Downie, read a piece in The Guardian by Glasgow Museums’ curator of British Art, Joanna Meacock (and active member of SWARN), about Joan Eardley’s Two Children, in Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Gallery.

This inspired her to interrogate Eardley’s Two Children painting, which many will know from visits to Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Art Gallery.

With the backing of Anne Morrison-Hudson and Glasgow Museums, Downie worked with child models of similar ages to the wee girls in this late unfinished painting found in Eardley’s Glasgow studio after she died.

The result was a new 21st-century version of an old favourite in which two children become four. One of the wee girls is even wearing silver boots.

We even have an illuminating new book, written by Patrick Elliot, Joan Eardley: Land & Sea – A Life in Catterline. A must-read for all Eardley fans.

Other happenings included weavers at Dovecot Studios in Edinburgh creating a stunning tapestry based on Eardley’s 1959 painting in the collection of the City Art Centre, July Fields while an Eardley poetry competition turned into a book called All Becomes Art: Poems to Joan Eardley.

For all those involved with Eardley 100, it was a joyous and occasionally feverish voyage of discovery. New nuggets about her life and work emerged as the year rolled on. They continue to emerge. New fans and admirers across the globe continue to join our merry throng on social media.

Today, on what would have been Joan Eardley’s 101st birthday, we would like to thank each and every one of you who contributed to a centenary like no other. We like to think we broke the mould.

So for now, without further ado, raise your glass if you will, to one of the greatest British artists of the last one hundred years.

Jan Patience

Arts journalist and co-founder of Eardley 100

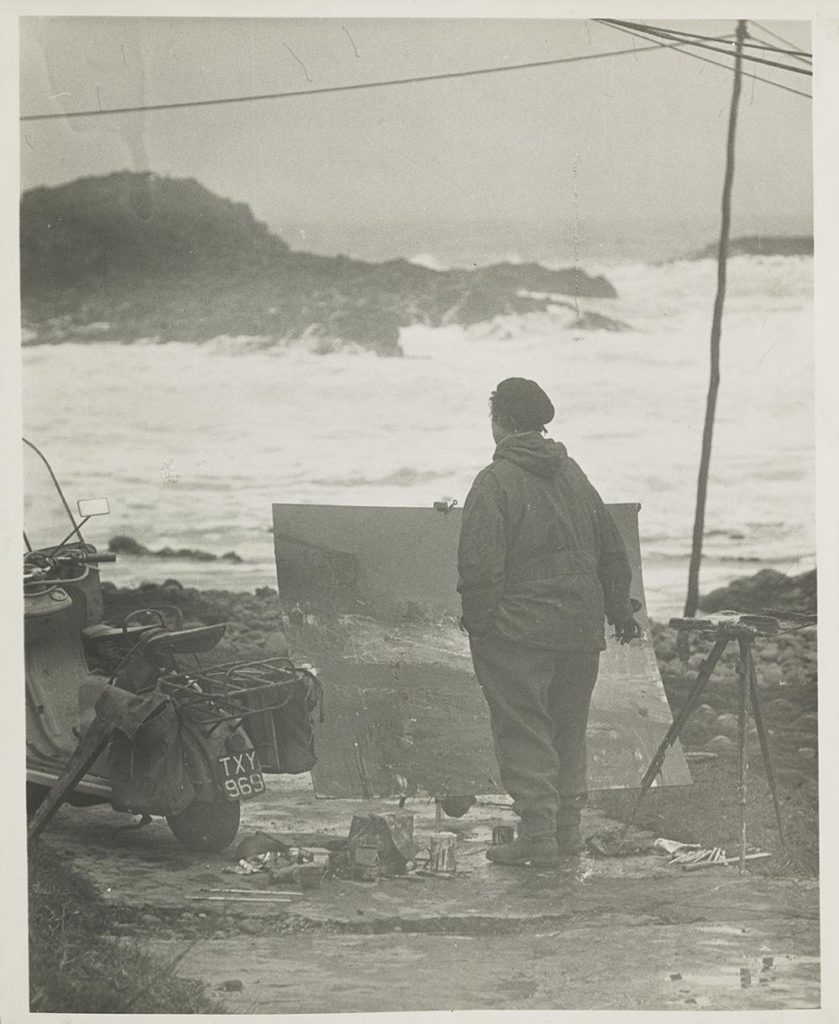

Photograph by Audrey Walker.